Search any library of stock images – the millions of pictures shot by hopeful photographers and resourceful graphic designers – for ‘agri-tech’, and you could be forgiven for thinking every crop from tomatoes to corn, strawberries, potatoes and rice is widely grown using robots, apps and driverless tractors.

The ‘farmers’ are resplendent in spotless white coats, or perfectly attired in ‘traditional’ plaid shirts, administering their domains from futuristic interfaces clearly inspired by the films Minority Report or Mission Impossible, with their mid-air gestures and holographic displays.

The reality, of course, is that all this imagery bears as much resemblance to even the most advanced of today’s operations as the – sticking with cinematic analogies – 2015 depicted in Back to the Future did to the ‘real’ 2015.

But perhaps each image could carry a tagline – ‘inspired by what may be’, or similar. Because, despite the fantasy inherent in many of those images, there is a grain of truth behind them: agriculture, one of the world’s oldest and most vital industries, will benefit greatly from the application of modern, disruptive technology.

It just won’t happen overnight, as many of the investors who were hoping to make a quick return on their agritech investments have since discovered. Agriculture is a game played for the long-term, with its developments measured in years or even decades. After all, the typical crop farmer, harvesting annually, might get just 30 chances – one a year – to test out new technology and see whether it works. That’s before he or she accounts for all the other variables that might also affect the outcome of his planting, such as weather, pests, disease, soils and the ever-changing dynamics of commodity markets.

So, in evaluating trends, it’s constructive to look at the bigger picture: what are the technological headwinds, advances, or economic or social trends, that are worthy of consideration for their effect in agriculture? And how do these shake out in identifying the ‘real’ trends that might come to define the agritech sector in 2025?

By analysing and comparing commentaries and opinions from across the sector, we’ve picked three trends that appear to have a degree more substance than a stock image alone.

1 – Artificial intelligence and machine learning, with precision farming and IoT

Why are there more myths and misconceptions about AI and its potential than any other recent technological introduction? Probably because the ‘powered by AI’ tag has been massively overused in the last 12 months, with even simple steps of logic now being dressed up as AI.

But dig a little deeper and we find that there are indeed ‘real’ applications for AI in agriculture. During 2024, we saw AI move from simple chatbots to far more sophisticated Large Language Models (LLMs), which can show some degree of autonomous behaviour, boosting the ability of farmers and their advisers to analyse farm data streams and improve decision making.

These LLMs will help increase profitability and productivity, using predictive analytics to help plan crop cycles, or to automate the machinery deployed on time-consuming (and expensive, in labour terms) tasks of planting and harvesting. AI can further advance the adoption of precision farming, ensuring the application of finite (and expensive) inputs such as fertilisers and crop protection products at the right time, in the right place and in the right amounts.

By bringing together these multiple streams of data – soil analysis, weather forecasts, pest and disease monitoring, crop health status, satellite imagery – AI will provide farmers with bespoke crop management strategies to optimise efficiencies.

Then there’s ‘digital twins’: described by some as the ‘untapped frontier’, a digital twin is a virtual replica of the real world, providing unlimited opportunities for simulation and prediction (certainly more than the 30 available to the average farmer over his career). Already widely used in healthcare and manufacturing to test ‘what if’ scenarios, in agriculture the digital twin roll-out has stuttered. But in 2025, better availability of data and improved integration looks set to help this valuable tool become more widely used.

And the data that brings all these together? It’s collected and delivered by the Internet of Thing (IoT): smart sensors, drones, weather stations – one researcher has even developed a system that effectively takes data from the crop itself. These are all connected to the internet and able to provide real-time, live data: the ‘feedstock’ for successful AI.

2 – Regenerative farming

Even if you’re not immersed in agriculture every day, there’s a fair chance you’ve heard of this term, as it gains traction and food companies begin to describe their products as ‘grown on regenerative farms’ or similar.

In short, it represents a shift in the agricultural mindset, from short-term to long-terms; from a focus on yields, towards long-term sustainability. In regenerative farming, it’s all about the soil: keeping it healthy through practices that also boost biodiversity and reduce the need for artificial inputs and interventions.

While it began as a true – and literal – grass-roots movement (grass plays a big role in regenerative farming, as a cover crop and as grazing to put livestock back into the cycle), it’s now attracted attention from governments (carbon capture) as well as leading food brands.

The global food giant Unilever, for example, has committed to rolling out regenerative agricultural practices across one million hectares of farmland by 20301. It’s already reached 350,000 ha of its target, across key crops such as soybeans in the US and Brazil, and oilseed rape in the UK and Europe1. Through regenerative agriculture, Unilever hopes to ensure its supply chains feature sustainable practices, end to end.

Here, data capture and application plays a big role too: AI, and its deployment in digital twins, has helped farmers tailor their management decisions to deliver the greatest effects on key metrics such as soil health and biodiversity – implementations that would previously have taken decades to assess, owing to the huge variations in local conditions and ecological needs.

3 – Controlled Environment Agriculture (CEA)

On first sight, the concept of growing crops in an indoor environment, under LED lighting and precision-controlled watering, might seem very far removed from the regenerative trend.

Yet there’s much in common. Also known as vertical farming, CEA allows crops to be grown year-round, or even several times a year, under near-perfect conditions. By precision management of all inputs – right down to the specific wavelength of the lighting – CEA can get the very most from each crop while minimising the use of precious resources.

Unused nutrients can be recovered and recycled in the closed system, rather than being lost as pollution to the atmosphere or into watercourses. And by excluding everything but the plants from the growing environment, pests and diseases can be eliminated without the need for fungicides or insecticides.

CEA is particularly attractive in helping to solve food security concerns. It can bring production closer to city centres (55% of the global population is urban), without the costs associated with transportation. It also offers hope for greater domestic food production in countries such as the United Arab Emirates, where climate and water scarcity makes conventional outdoor agriculture almost impossible.

Yet it’s not suitable for all crops. Growing a crop of wheat under CEA conditions is possible, with far higher yields, in far shorter time. But our demand for wheat is such that we simply wouldn’t be able to construct the facilities required; costs would be prohibitive. So the technology’s largely been limited to high-value, quick-growing and perishable crops such as herbs or leafy greens. But as the technology matures, more crops – tomatoes, soft fruits such as strawberries – will become more widely grown under CEA conditions.

Of course, these are only the predictions of others. But it’s noticeable that across all the ‘start of year’ punditry we reviewed and analysed, there were no real outliers: a word cloud would feature ‘data’, ‘AI’, ‘precision ag’, ‘regen ag’, ‘sustainability’ and ‘digital’ as the most prominent mentions. That would suggest that the pundits at least agree on the rough direction in which agritech will head over the next 12 months.

Then again, as a wise man once said, “Pundits should always be ignored.” And as Steve Jobs himself demonstrated, the best way to predict the future is to create it: the whole smartphone category, is testament to that truth. Will 2025 reveal agritech’s own disruptive moment?

Why stick to one fuel, when you can have a configurable power system?

Read moreMore than just a curiosity, they offer us different routes to future food security.

Read morePerkins marine engines has an illustrious history. Meet the team behind the brand.

Read morePower systems, services and technologies engineered for efficiency, productivity and fuel flexibility will be on show.

Read moreDelivering dependable prime and standby solutions with the 13 litre 2606 and a 46 litre 5012.

Read morePerkins has announced a power uplift to the popular 3.6 litre variant.

Read moreWe chat to Corey Berry following the successful showings at American Rental Association (ARA) and United Rentals exhibitions.

Read moreWe headed to Malaga, Spain, to learn more and see the machine in action.

Read moreThe Perkins marine distributor network is there to service customers of Perkins anywhere in the world.

Read moreAvailable in the second half of 2025, the 2600 Series offers excellent load acceptance, fuel efficiency and versatility.

Read moreHow our Customer Solutions and Engineering teams are actively helping customers reduce fuel consumption.

Read moreThe state’s farmers grow more than 400 commodity crops, 19 of them unique to the Golden State.

Read moreMore than 280,000 visitors from across the world attended this year’s four-day long Bauma China exhibition in Shanghai.

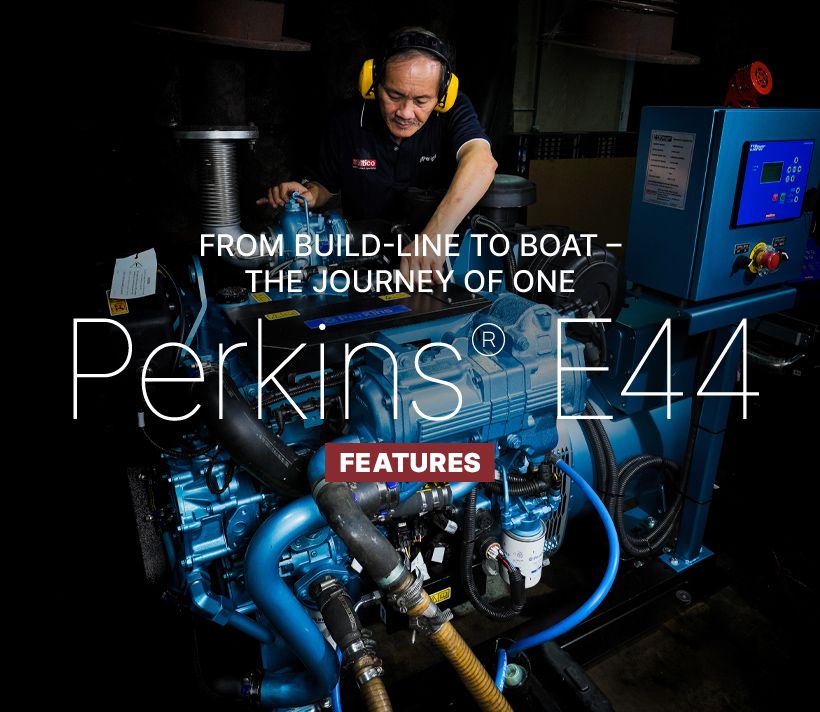

Read moreWe follow the journey from a Perkins facility in the UK to installation on a passenger ferry in Singapore.

Read morePowernews caught up with Sylvia to learn more about her responsibilities, motivations, and leadership journey.

Read moreA new range of auxiliary marine engines were shown at METS.

Read moreAdrian Bell dives into the history of Californian agriculture.

Read moreThe importance of thermal fluids simulation.

Read moreHow ‘noise chambers’ help Perkins build quieter engines.

Read moreThe global voice for agricultural equipment manufacturers.

Read moreMeet our Vice President of facility operations.

Read moreThe customer benefits achieved through Perkins’ new connectivity solutions.

Read moreThe new Perkins global marketing and channel development director.

Read moreThings are different when it’s very, very cold.

Read moreEngineering manager Graham Hill explains the importance of structural simulation when designing a new engine.

Read moreThe platform will cover two key power nodes.

Read moreInterview with Susterre CEO Michael Cully on the latest no-till soil solutions.

Read moreA compact 12 cylinder powerhouse.

Read moreFor 60 years Lindner has chosen Perkins engines to power its machines.

Read moreTwo new auxiliary engines powering the marine sector.

Read morePerkins kicks off Project Coeus to demonstrate leading-edge hydrogen hybrid power solutions.

Read moreDependable electric power generation drives sales of Perkins® 4000 Series in India.

Read morePerkins launches the next generation 2600 Series engine.

Read moreAdding to the product range with an 18-litre engine.

Read moreFind out how this vast country approaches agriculture and food production.

Read moreBy re-examining, reimagining, and re-engineering what is expected.

Read moreA clear demonstration of what's possible when a passion for innovation meets a commitment to excellence.

Read moreWith local resources and global support.

Read moreAdvance power solutions from Perkins.

Read morePart three of our series with Dave Robinson.

Read moreJaz Gill talks Perkins new brand strategy.

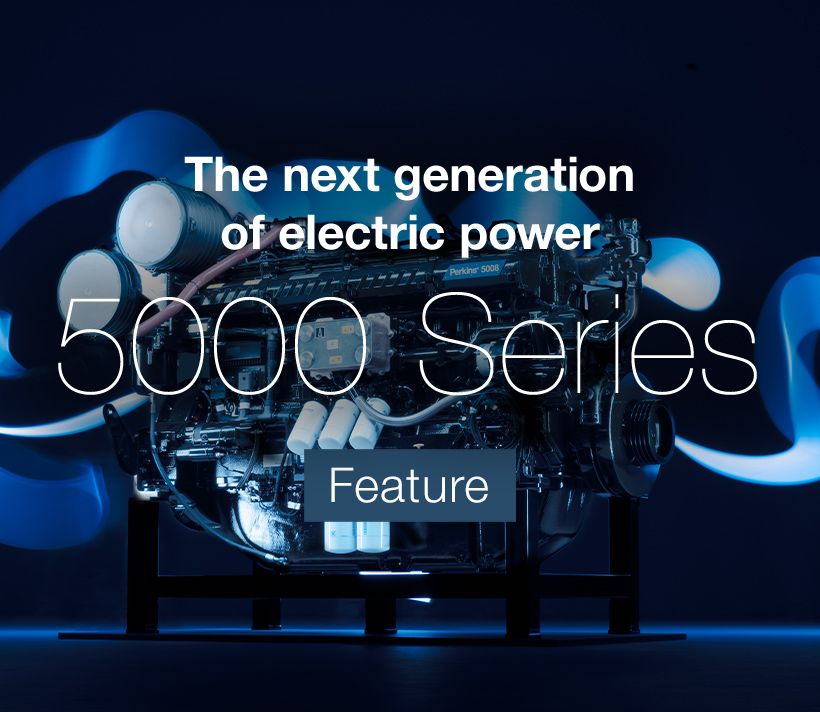

Read moreThe Perkins® 5000 Series engines generating reliable power for critical applications.

Read moreRental expert Dave Stollery gives his view on the opportunities around rolling out EU Stage V equipment.

Read moreIf you want to get back to engineering, this programme can be the key to making it happen.

Read moreConstantly innovating to meet the changing electric power marketplace.

Read moreAn appropriate environmental, social and governance (ESG) proposition really matters.

Read moreManufacturing industrial engines at our Curitiba facility since 2003.

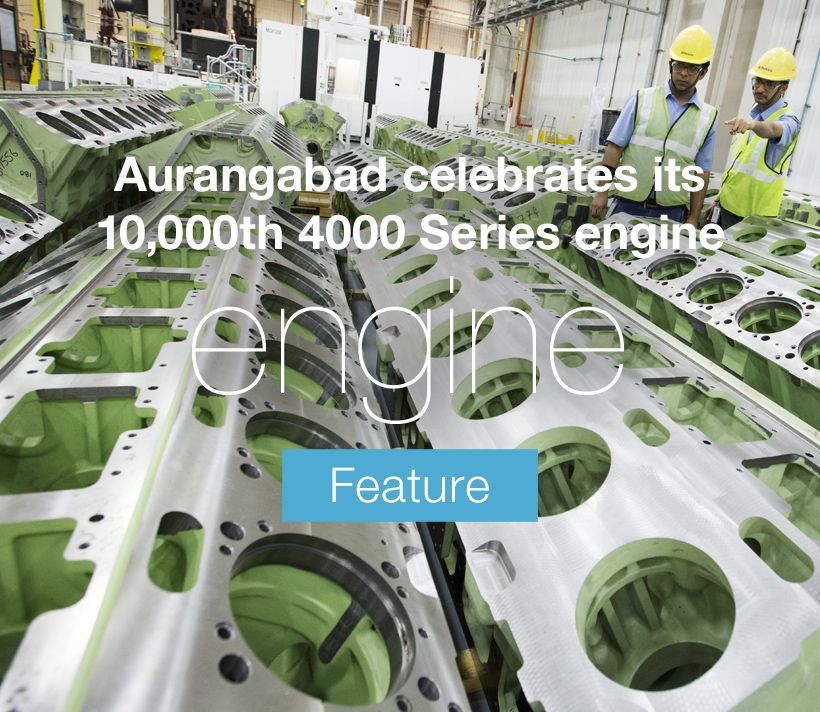

Read morePerkins Aurangabad celebrates the production of its 10,000th 4000 Series engine.

Read moreThe heart of sustainable power.

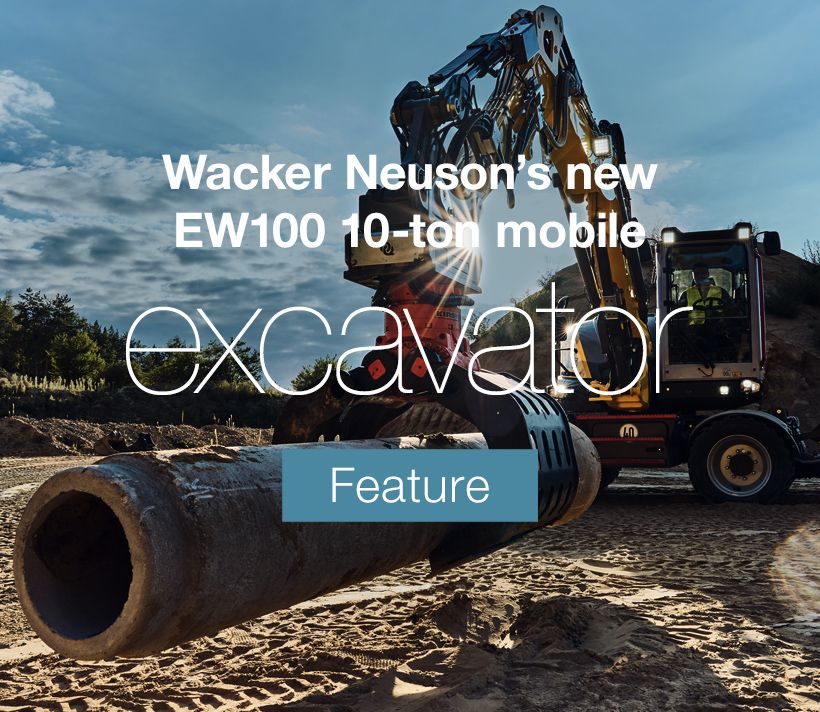

Read moreWacker Neuson’s new EW100 10-ton mobile excavator

Read moreOffering a complete solution for off-highway engines in Latin America.

Read moreFifty years of support for the written word in agriculture.

Read morePerkins rental industry commitment continues to grow.

Read moreRenewable and low carbon intensity fuels in Perkins engines.

Read moreSupporting the STEM development of future generations.

Learn MorePart 2 of our three part interview series with Perkins’ Dave Robinson.

Read moreThe launch of the complete range of 5000 Series full authority electronic engines.

Read morePerkins is actively supporting the rental industry's transition to the latest EU Stage V technologies.

Read morePowered by the compact and powerful Perkins® 904 Series.

Read morePerkins EAME business development director Dave Robinson writes on 'power on the farm'.

Read moreThe Perkins Rental Support Programme has already been adopted in some form by virtually every significant rental business in the world.

Read moreDid you know that Türkiye is the world’s fourth-biggest tractor market? Take a closer look – from an agricultural perspective – at this fascinating country.

Read moreThe Perkins® 904 Series family of Industrial Open Power Units provide customers with ‘plug-and-play’ engines that often can be fitted to a broad range of equipment.

Read moreThe Curitiba plant has delivered more than 300,000 engines since 2003 including engines meeting MAR-1 emission standards.

Read moreWhy the popularity of telehandlers is reaching new heights.

Read moreWhy data has become a priceless commodity in modern construction.

Read moreTalk of reaching ‘net zero’ is frequently discussed, but what does net zero look like for agriculture?

Read moreWhy the rental industry is so well placed to support sustainability goals.

Read moreWould you buy a diesel-powered mobile phone?

Read moreDiscover more about the benefits of moving to Stage V power.

Read moreWho will be the farmer of tomorrow and what skills will they have?

Read moreWhat role will this industry icon play in tomorrow's industrial world?

Read moreLow noise, vibration and harshness is important to both OEMs and the end user.

Read moreInsatiable demand for data in South Africa is driving a huge growth in data centres.

Read moreWhat does urban construction look like over the next decade?

Read moreThe electric charge: how access to reliable power is fuelling prosperity across the globe.

Read morePutting the shine on sustainability.

Read morePutting people into plant.

Read moreRevolution through evolution.

Read moreCollaboration: in search of excellence.

Read moreThe future of diesel-driven power generation keeps getting brighter.

Read moreWhat are the key benefits of downsizing engine capacity in the materials handling.

Read moreHow can manufacturing businesses move stock like clockwork?

Read moreImportant information and tips to make the best decision for your next job.

Read morePerkins has announced a power uplift to the popular 3.6 litre variant.

Read moreWe chat to Corey Berry following the successful showings at American Rental Association (ARA) and United Rentals exhibitions.

Read moreWe headed to Malaga, Spain, to learn more and see the machine in action.

Read moreThe Perkins marine distributor network is there to service customers of Perkins anywhere in the world.

Read more